Old Main: A Building for the Ages

The History and Architecture of Old Main

by Nora Pat Small

Castles have been a regular feature of midwestern college campuses since at least 1857 when Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, erected its main building with towers and battlements. Other medieval forms-- more church-like than castle-like-- appeared as early as 1827 at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, and in 1839 at Jubilee College on the Illinois frontier near Peoria.1 The castle that arose on Eastern Illinois State Normal School’s campus one century ago clothed then-modern values in what to us appears to be traditional garb, but was to contemporaries quite current. To its builders and occupants the school’s medieval form represented democratic ideals and sound morals, a fitting edifice for the education of future teachers. Broad cultural currents came together in the collegiate castles of the nineteenth century, including the association of the Gothic with christian morality, the aesthetic appeal of the picturesque, and the political triumph of democracy. We can see all of these elements at work in Eastern’s Old Main.

|

Battlements, towers, turrets, pointed arches, and label molds all are characteristic of the various Gothic revival styles. [Fig. 1] Unlike the original Gothic, where arches actually supported walls and battlements provided protection from marauders, these elements in their revived form were purely decorative. But the Gothic style remained a venerable tradition at institutions of higher learning. Having arisen out of certain social and economic conditions of the middle ages, it was only natural that the original university buildings assume the building characteristics of their time. Although many American colleges in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries turned their backs on this tradition, preferring to build in the more modern classical style, by the 1830s the Gothic again assumed a pre-eminent place on United States college campuses. Popularized by Alexander Jackson Davis, the “Collegiate Gothic” also represented a break from the rigid classical education that held sway at the oldest institutions. |

Fig. 1. Eastern's campus contains several variations on the Gothic.

1a. The Castellated Gothic: Old Main, completed 1899.

1b. Jacobean Gothic: Pemberton Hall, completed 1908, first occupied January, 1909.

1c. Jacobean Gothic: Blair Hall, completed 1913. |

The non-functional quality of many Gothic elements used on American buildings did not imply a lack of meaning or significance. Fifty years before Old Main was conceived, architects and many home-owners had decided that the Gothic, arising out of an indisputably christian era, represented perfectly the christian morality of that reform-minded age. As such, it was the style of choice for many churches and homes. In 1854 architect Edward Shaw published The Modern Architect; or Every Carpenter His Own Master in which he recommended Gothic churches both as indicators of “highly cultivated taste” and as structures guaranteed to arouse spirituality:

No one, who has within him a spirit that prompts him to worship God, can be insensible to an emotion nearly allied to that of religious reverence, when he approaches and enters a Gothic structure. . . . The lofty spire, pinnacles and finials, seem as so many fingers pointing upward to heaven, and directing his way thither. In the massive tower and battlements, the mind perceives an emblem of the stability of truth, and of the gracious promises of God, and is led to repose confidingly in Him. On entering, the mind swells with the feeling of sublimity, and seems, almost involuntarily, to rise in adoration of the Being who is himself so great, and has given to man the power to raise a temple so fit for His worship.2

As symbols of truth and “religious reverence” the Gothic tower, battlements and other decorative details would serve the purposes of higher education for decades to come.

The new normal school at Charleston, however, did not rely entirely on inspirational architecture to ensure the safety of its students’ souls. Having provided an appropriate setting, the school also required that students regularly attend their chosen churches, as well as daily chapel or assembly in the school’s assembly hall. In 1933 a former student, then college professor, recalled the chapel exercises of the first decade of the century:

Highest of all . . . do I prize the opportunity that was given to attend chapel exercises every morning for three years, for I believe that what I think and enjoy today was largely determined by those exercises. . . . Many of the things that I have seen and heard since that time have been subjected to measurement by the standards I formed during those chapel exercises.3

At chapel he and his classmates heard readings from literature and from the bible. They listened to visiting speakers as well as to school president Livingston C. Lord who, according to a collection of Lord’s sayings published after his death, admonished them to “Tell the truth and don’t be afraid,” and who expected “Attention, behavior, religion, morality, righteousness,” of himself as well as his students.4 In the case of Old Main, form truly did follow function, both by inspiring religious feeling and by providing space for moral instruction.

|

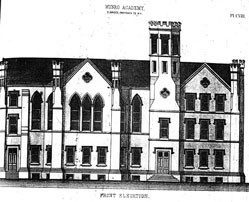

In addition to its christian associations, the picturesque, or scenic qualities of the Gothic style appealed to many who associated it with natural beauty. Uvedale Price, an English architectural theorist of the late eighteenth century, made that connection in On the Picturesque in 1795: “In Gothic buildings the outline of the summit presents such a variety of forms, of turrets and pinacles, some open, some fretted and variously enriched, that even when there is an exact correspondance of parts, it is often disguised by an appearance of splendid confusion and irregularity.”5 Such “splendid confusion and irregularity” corresponded with and embellished the natural, albeit artfully improved, landscape in which a Gothic building was set. Americans became enamored of the romantic effects of picturesque architectural and landscape treatments in the nineteenth century. Architectural pattern book authors such as Minard Lafever popularized the forms in their publications. In 1856, for example, Lafever published his designs for the Munro Academy in Elbridge, New York. This Gothic-style school building he described as standing “in an open landscape. . . surrounded by trees, which with the irregularity of the plan and outline of the structure itself, contribute to its picturesque effect.”6 [Fig. 2] Two decades later English architect Charles Eastlake again reinforced the suitability of combining Gothic forms in a rural setting to create a picturesque effect: “The classic Picturesque building type was of course the Gothick castle, or rather the country house ‘in the castle style.’” He concluded that the Picturesque had affected architecture by encouraging “pictorial qualities at the expense of architectural qualities: movement, irregularity, contrast, mystery, romance and texture. . .”7 Those pictorial qualities recommended the style to natural settings. |

Fig. 2. Munro Academy, Elbridge, New York; from Minard Lafever, The Architectural Instructor, 1856. Lafever created a picturesque effect through the use of an irregular roofline and plan. |

The acknowledged picturesque qualities of the Gothic, that is its suitability for use in scenic environs, corresponded well with the growing popularity in the United States of locating colleges in the countryside. Over the course of the nineteenth century, as architectural historian Paul Turner has pointed out, the motivation for building colleges in non-urban areas changed from a desire to avoid the vices of the city, to an actual preference for the aesthetics and supposed higher morality of rural life.8 In 1878 Charles Thwing opined that if the large urban colleges (Harvard, Yale, Columbia) were located in smaller rural towns, “the moral character of their students would be elevated in as great a degree as the natural scenery of their localities would be increased in beauty.”9 The picturesque qualities and moral character of the Gothic and the rural meshed perfectly on many American campuses. Governor Altgeld recognized these qualities of rural life in his speech at the laying of the corner stone for the new Normal School in May, 1896. Eastern Illinois, he said, had

escaped the intensified form of vice, misery and disintegration of society that are peculiar to centers of population. Dollars may grow in cities but men grow nearer to nature. . . . The nearer we get to nature the higher we rise in the conception of the world. Here is the place to found schools and academies. Fields and forests, bright suns, blue skies, and the eternal stars all suggest purity and tend to elevate the soul of man, while the whisperings of nature cause the human heart to reach out after the architect of the universe.10

|

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Gothic mode had become an alternative to the mechanical and the industrial. It called to mind a time of hand-crafted goods and communal society, in contrast to the mass-produced goods and growing impersonalization of transactions in late-nineteenth-century America. As such, it played a role in the American Arts and Crafts movement. Indeed, the Gothic Revival of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century corresponds with the zenith of that craft-oriented movement. The two movements shared many aesthetic and moral assumptions-- deceit was bad, therefore structure should be visible; nature was an excellent source of design motifs and therefore the artificiality of the classical was reprehensible; vernacular art and architecture were more natural, therefore Europe’s medieval Gothic, Native American and the United States’ colonial inheritance were worthy of emulation. [Fig. 3] |

Fig. 3. Old Main, north entrance. The Gothic frequently employed motifs inspired by nature, such as these foliated capitals. (Richard V. Riccio, photographer) |

Architect Ralph Adams Cram was one who argued forcefully for a revival of the Gothic spirit. In 1916, in the midst of the most devastating war the world had ever known, Cram delivered a series of lectures on the Gothic in which he gave voice to the democratic, as well as the christian, qualities of Gothic architecture. In the Middle Ages, he declared, before the division of society into capitalists and proletariat, communal society, and hence communal art, had flourished. This art grew from the “spontaneous demand of a whole people.” Its democratic nature was evident in the lack of hierarchy in the building trades and in the co-operation among artists and craftsmen, none of whom dominated the others. “Mediaeval architecture was the work of free, proud, independent artists and craftsmen, working together, each in his own sphere, and all to the common end of producing something better and more beautiful than had ever been seen before.”11 Because of its origins in what Cram regarded as a demonstrably more christian and democratic society, Gothic architecture served as a proper symbol of the Church’s and university’s fight against “their eternal enemy, the new paganism.” That translated in 1916 as the “Capitalistic and Industrial State.”12 By modern scholarly account, Mr. Cram was considerably off the mark, yet his perception of the nature of mediaeval society was deeply engrained in American popular culture. The supposedly democratic nature of the Gothic was in marked contrast to what many viewed as imperialistic architectural classicism that predominated at the time of Old Main’s construction.

That imperialism was nowhere more evident than at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Presided over by east coast architects the Fair created a visionary White City dominated by monumental classical structures arrayed along carefully planned boulevards. The Columbian Exposition prompted the City Beautiful movement in which city planners proposed transforming cities into monuments to urban culture and civic pride by thinking big. Cultural institutions would dominate the cityscape with imposing classical structures which would line and terminate broad boulevards. In spite of the financial panic that engulfed the nation just as the Fair opened, the World’s Columbian Exposition was a smash hit. While the displays and the technology dumb-founded those who attended, the Exposition also appealed to Americans at another level. As architectural historian William Jordy has observed,

[T]he imperial flavor of the White City accorded with the imperial flavor of American culture at the end of the century. It was not merely, or even principally, the imperialism of foreign affairs which the symbolism of the Exposition made concrete, but the hegemony of the metropolis over the farm.13

But the ideas of imperialism and urban dominance did not appeal to all. Architectural critic Lewis Mumford, having observed the results of this type of urban planning and architecture, was particularly harsh in his judgement of 1924:

Our imperial architecture is an architecture of compensation: it provides grandiloquent stones for people who have been deprived of bread and sunlight and all that keeps man from becoming vile. Behind the monumental facades of our metropolises trudges a landless protetariat, doomed to the servile routine of the factory system; and beyond the great cities lies a countryside whose goods are drained away, whose children are uprooted from the soil on the prospect of easy gain and endless amusements, and whose remaining cultivators are steadily drifting into the ranks of an abject tenantry.14

The Eastern Illinois Normal School had to tread a fine line between grandiloquent monumentality that could lead only to depravity, and mean simplicity that would suggest lack of pride and sensibility. It had to celebrate the rural, for its purpose was to educate teachers for rural schools, without denying the importance of cultured taste. If classicism had come to represent the triumph of imperialism and urbanism, then the Gothic, in addition to symbolizing christianity and rural simplicity, also represented democracy, on which principles the normal school movement relied heavily.

Beginning in the 1840s education reformers demanded more democratic institutions that served the needs of the general population, and not just an economic or political elite.15 This movement spawned both the demand for public normal schools and more wide-ranging curricula at older, established colleges. More democratic schooling consisted of less time spent on the classics and ancient languages, and more time spent on sciences, mathematics, history, and the fine arts. Illinois responded to the push for normal schools for the first time in 1857. By the time Eastern Illinois Normal School was dedicated, the state had committed to supporting five such institutions. At the dedication of the new Eastern Illinois Normal School on August 31, 1899, Dr. Richard Edwards celebrated the institution’s democratic origins, as Governor Altgeld had proclaimed the glories of rural life at the cornerstone laying three years earlier, “The Normal school is the highest exhibition of the idea of universal education. And the idea of universal education has at its basis the great principle of human equality.”16

Ensuring the quality of education for all Illinois residents went hand in hand with producing teachers who were themselves model citizens, and who could in turn instill American values in their rural charges. Governor Tanner stated that mission clearly in his dedication day speech in Charleston: “treason and infidelity were never taught in our public schools, but principles that led to love of country, love of flag, love of God.” Echoing the thoughts of Dr. Edwards, the governor proclaimed, “There is reason why our people cherish so fervent an interest in their public schools. It is a reason based upon the conviction that somehow universal education is essential to the perpetuity of the republic.”17

Educators and politicians alike believed that the normal schools should promote democracy and patriotism. Governor Tanner, in addition to advocating agricultural science studies, emphasized the need for the curriculum to address civic affairs,

I desire also to call attention to the provision in the act establishing this school which requies that instruction shall be given ‘in the fundamental laws of the United States and of the State of Illinois, in regard to the rights and duties of voters.’ The boys should be taught that they have no more right to let politics alone, the science of government, than they have to let their daily labors alone.18

In 1901 the president of Eastern, Livingston C. Lord, received a letter from the Illinois state superintendent of public instruction asking which question he thought the next meeting of the Schoolmasters’ Club should address-- “‘Shall we advise individual or class teaching?’”19 or “‘Are the common schools conservators of democracy?’” If the answer to the second question was “yes,” then the state normal schools had to be sure they turned out teachers well grounded in democratic philosophy, politics, and history.

In the waning years of the nineteenth century, the Gothic had much to recommend itself to the Indianapolis architects, McPherson and Bowman, who undertook the initial design for the new normal school at Charleston. It had venerable origins which recommended it to modern churches and colleges alike; it represented secular and religious values simultaneously; and it was well suited to a rural setting for both aesthetic and social reasons. It could be commanding without being perceived as over-bearing. Whatever had inspired McPherson’s and Bowman’s design decisions, they did not make those decisions in a vacuum. They, and the public that would view and use the new normal school, understood the aesthetic and associative value of the Gothic.

|

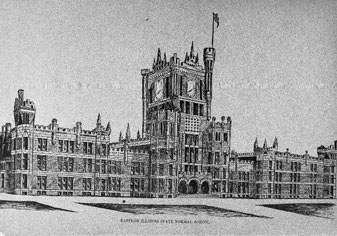

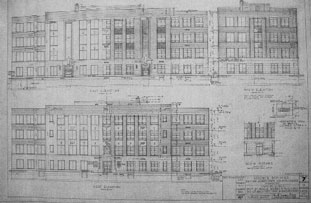

The building that finally housed the normal school diverged from McPherson and Bowman’s original vision, but because no original drawings survive it is impossible to tell exactly what changed and when. [Fig. 4] We do know that the normal school trustees accepted McPherson’s and Bowman’s plans on October 5, 1895. In response to objections raised by Governor Altgeld, the firm altered their designs, but those, too, proved unsatisfactory. One suspects that the governor disapproved of the Indianapolis firm for some reason, rather than their designs, because the trustees accepted the plans drawn up by architect George H. Miller of Bloomington, Illinois, with only “slight alterations and modifications from those offered by Bowman and McPherson.”20 In December, 1895, Angus and Gindele of Chicago signed a contract with the normal school to construct a building according to the revised plans, drawings, and specifications of McPherson and Bowman. Those revisions had been undertaken by architect L. B. Larmour, but the contract specified that the actual construction work be done under the supervision of George H. Miller. It is nowhere indicated that Miller had a hand in that particular round of revisions. |

Fig. 4a. The original design for Old Main may have been rejected because its elaborate finish negated the frugal qualities of Gothic architecture that appealed to Governor Altgeld.

Fig. 4b. The normal school as built, c. summer of 1899. |

|

By March, 1896, Angus and Gindele realized that they had bid on the wrong designs. Sometime before March 5 they received drawings from Miller and Fisher which they took with them to Charleston. Unfortunately, they then discovered that “the plans would not suit the lay out of the ground and it would be necessary to carry foundations down deeper. . . .”21 They wrote to the building committee of the normal school stating that they would adjust the foundations and lower walls, and change the water table as well as the battlements on the porch, main tower, and “entire building” if the committee would accept other changes that would save the contractors some money. The design had not, apparently, assumed its final appearance at the time of the laying of the cornerstone on May 27, 1896. All of the illustrations of the building preserved in the cornerstone time capsule show a more elaborate roofline than was ultimately built. Because the surviving specifications refer constantly to the missing drawings, we cannot discern exactly when the normal school’s final appearance was decided, nor by whom. It may have been early in 1897 when the contractors pleaded with the building committee to allow them to make changes, or the final adjustments to the battlements and towers may have come when Angus and Gindele failed financially and local contractor Alexander Briggs assumed responsibility for completing the job in September, 1897. At that time, too, the project acquired a new architect, Charles Ward Rapp of Chicago. [Fig. 5] Rapp, who as a member of the firm Rapp and Rapp would go on to make a name for himself in theater design circles, came from Carbondale, Illinois, where he had already designed Altgeld Hall for Southern Illinois Normal University. [Fig. 6] |

Fig. 5. Plan, second floor, Old Main; Charles Ward Rapp, architect.

Fig. 6. Altgeld Hall, Southern Illinois Normal University, Carbondale, Illinois; Charles W. Rapp, architect. (Altgeld Hall on right; Archives, Southern Illinois University-Carbondale). |

However Old Main acquired its final appearance, when the school opened for business in 1899 its letterhead featured a more elaborate version of the building than was actually constructed. Looking closely at this fancy variation, one finds that Old Main as built differed only superficially from the more ornate design. With fewer turrets and no spires or clock in the central tower, the Eastern Illinois State Normal School nevertheless retained the footprint and fenestration patterns of the earlier design. In good picturesque Gothic fashion the school featured an irregular outline with its battlemented towers and turrets. It also, however, presented a stolidly symmetrical facade to the world, its centrally located entrance tower framed by matching wings. Here, surely, was a nod to both urbane culture and conservative rural values.

Although simpler, and perhaps even austere in comparison to the proposed structure, Old Main was still an edifying, and far from simple, structure. The Charleston Daily Courier published a description of the building on its dedication day that offers us a glimpse of its sumptuous quality. The vestibule of the main entrance was “finished in a beautiful shade of red, set off with black figures, relieved by gilt tracings. The vestibule ceiling is in gold and ivory with gold relief work and decorations.” The ceiling in the first floor corridor was “divided into thirteen panels, decorated in a most artistic manner, a striking feature being five allegorical figures, which alternate with panels of floral decorations. . . .” The walls in the President’s room were lavendar with green figures, the ceiling ivory and gold with garlands and gold relief work. The assembly hall they judged “truly a gem of the decorative art” with its paneled ceiling and stenciled walls.22 The new normal school was in every way a public monument. Imposing and tasteful, it provided all the necessary and practical spaces while striving to raise the artistic and cultural sensibilities of students and visitors alike.

The presentation of a refined public face did not end at the walls of the school. The school needed a proper picturesque landscape to set off its scenic qualities, and emphasize its association with nature and all that would imply about rural healthfulness and morality. With the proper landscaping, the entire campus could become a source of inspiration and education. The natural advantages of this site were not lost on the Charleston Daily Courier reporter who covered the dedication ceremony: “The building is admirably situated on a plateau,” and “The campus is a beautiful piece of the Creator’s work, extending over forty acres, nicely interspersed with natural shade.” Part of the C.E. Bishop farm, the natural beauty of the wooded parcel evidently impressed the trustees of the new Eastern Illinois Normal School charged with final site selection.

Picturesque beauty, however, usually required human intervention to reach its full potential, and the normal school grounds were no exception. The Charleston Daily Courier reported that nature could, and probably should, be improved upon.

|

The natural beauty has already been greatly enhanced by driveways of crushed stone, concrete walks, flower beds, in beautiful designs, etc. As time goes on, the grounds will be steadily improved and beautified by the plans drawn up by Mr. DuBois of Peoria, till it will be a most attractive and beautiful place.23 [Fig. 7] |

Fig. 7. DuBuis Landscape, Plan 1899. Mr. DuBuis (also spelled DuBois) devised the initial landscaping for the school grounds, which was superceded by the 1901 Walter Burley Griffin plan. |

The plan drawn up by Mr. DuBois did not long serve as the blueprint for campus landscape development. By October, 1901, President Lord had received specifications for the improvement of the grounds of the normal school from Walter Burley Griffin. Griffin, who had graduated from the University of Illinois’ architecture school in 1900, evidently drew up the plans for Eastern Illinois while employed in the Chicago office of Dwight Perkins. As with Old Main, no drawings are known to survive, but Griffin, like his Prairie School compatriots, designed with the character of the prairie and its native plants in mind.24 The extent to which Griffin’s plan survives is currently unknown, but in 1925 Ernest Stover, a member of the Botany Department at the Eastern Illinois State Teachers College, wrote that “The college is indebted to the noted landscape architect, Mr. Walter Burley Griffin, for the original plans for this campus, and to Mr. Walter H. Nehrling for his skill and care in keeping the campus one of the beauty spots of this region.”25

The same year that Griffin provided his landscape plans, the normal school catalogue announced that “A school garden is being arranged for and is to be constructed on the plan of the school gardens of France and Germany.” The gardens did not serve only as pretty landscaping. They became a part of the students’ education, as the school intended to “interest its students in the culture of both flowers and vegetables, and to encourage them to beautify the grounds of the schools in which they are to teach.”26

Griffin also designed a greenhouse for the school before 1902, which was rejected as being too costly. A less expensive greenhouse was built and available for use by spring term of 1903. Like the landscaped grounds, the greenhouse fulfilled both educational needs, in the form of material for the botany classes, and aesthetic goals, by providing plants for “beautifying the school rooms and grounds.”27 As a letter from an alumnus testifies, these efforts were not in vain. Recalling his training at Eastern Illinois State Normal School a college professor wrote,

I am convinced that the most valuable contributions to my education were made by this small teacher-training school. . . . the physical setting of the school fostered an appreciation of the beautiful. I can yet see the campus and the Normal School building as they appeared to me, a raw country school teacher. . . . To some a medieval castle may seem out of place at the edge of an Illinois prairie, but its appeal to the fancy of youth is, I am sure, more uplifting than that of our modern utilitarian structures.28

When this anonymous author completed his work at Eastern in 1908, the campus plantings had matured for nearly a decade and ivy mellowed the school’s stone walls. The castle on the prairie had accomplished what it was designed to accomplish-- inspire students through both their physical setting and their intellectual pursuits.

When that student took his leave of Eastern Normal School, the campus did not yet have its second major academic building. President Lord, in a letter of May, 1903, asked for Griffin’s opinion on where the gymnasium should be located, to which Griffin replied

As to the gymnasium site perhaps new conditions have arisen since it was formerly considered otherwise as far as I am able at present to see the old location beyond the west edge of the quadrangle [illegible] is the logical one, in general, to be more exactly fixed through consideration of the trees and the design of the building which latter it seems to me should conform to the old group, in a sense, to become part of the family, at least not a foreigner.29

|

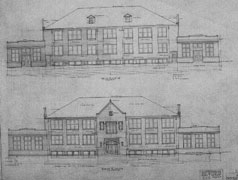

Pemberton Hall was completed in 1908 along with its gymnasium, which, indeed, conform to the design of the original building. Pemberton’s architect chose a Tudor Gothic mode, complementary to, but not imitative of, Old Main’s castellated Gothic style.30 The school continued its collegiate Gothic style with the construction of Blair Hall (1911-1913), and the Practical Arts building in 1929, but succumbed to modern rejection of overtly historical styles in the 1930s with the construction of the Health Education building and the Science building. [Fig. 10] The last Gothic building on campus would be Booth Library, completed in 1949. [Fig. 9] |

Fig. 8. Variations on the Gothic dominated campus architecture in the school's first thirty years. In the 1930s, the ahistorical Art Deco style came to campus in the form of the Science building (1937) and the Health Education building (1936).

Fig. 8a. Model School Building (Blair Hall).

Fig. 8b. Practical Arts Building (Student Services), north elevation; William J. Lindstrom, supervising engineer, 1927. |

Fig. 8c. Health Education Building, east elevation; C. Herrick Hammond, architect.

Fig. 8d. Science building; C. Herrick Hammond, architect. |

Fig. 9. Booth Library, c. 1949. |

In 1899, the castellated Gothic of the normal school created instant venerability and respectability. Over the years, however, people lost sight of the meaning of Gothic castles on college campuses. In 1936 a committee of the Illinois senate concluded,

The castle type of construction-- all honor, nevertheless, to the sturdy Altgelt-- is not an ideal architecture for education. These castles. . . are not kept in repair, either inside or outside. There is not a school of the five where new buildings are not badly needed.31

Succeeding generations may have forgotten the original intent of the Gothic design, but Old Main, nonetheless, grew into a venerated landmark, the institution into a well-respected one. Old Main speaks volumes about the people who commissioned and designed it. Just as we can read the building to discern something of that era’s values and aspirations, so might current and future generations read the building to determine our own priorities and sensibilities. Does the building as it stands today convey a sense of respect for the institution it has come to represent? Does its condition suggest a veneration of the past, of the hundred years of history that have created the current university, or a short memory?

|

The Livingston C. Lord Administration Building must fulfill a challenging mission. It must serve as both icon and working structure. It must meet current needs without losing its historic character. Eastern Illinois University is a very different institution from the Eastern Illinois State Normal School opened here one hundred years ago, but without the physical reminders, without the historic landscape, it is difficult to remember or care where we came from, why we changed. [Fig. 10] |

Fig. 10. In spite of changes in Eastern's mission and Old Main's function, Old Main remains the icon of Eastern Illinois University. Old Main's central tower. |

Nora Pat Small

Eastern Illinois University

September, 1999

1. Turner, Paul Venable. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), 114, 121.

2. Shaw, Edward. The Modern Architect: A Classic Victorian Stylebook and Carpenter’s Manual. (Boston, MA: Dayton and Wentworth, 1854; reprint New York: Dover Publications, 1995), 94-95.

3. “Letter from Alumnus Reveals True Appreciation of E.I.,” Teachers College News. (Charleston, IL, May 23, 1933), 5.

4. Ibid.

5. As quoted in John Gloag, Victorian Taste: Some Social Aspects of Architecture and Industrial Design, from 1820-1900. (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1962), 11.

6. Lafever, Minard. The Architectural Instructor, containing a History of Architecture. (New York: G.P. Putnam and Co., 1856), 495.

7. Charles L. Eastlake, A History of the Gothic Revival, ed. J. Morduant Cook (1872; reprint New York: Humanities Press, Leicester University Press, 1970), 50, 54.

8. Turner, 101.

9. Charles Thwing, American Colleges: Their Students and Work (New York: G. P. Putnams’ Sons, 1878), 48.

10. “Laying of the Corner Stone” (Charleston Courier, May 28, 1896), 4.

11. Ralph Adams Cram, The Substance of Gothic: Six Lectures on the Development of Architecture from Charlemagne to Henry VIII (Boston, MA: Marshall Jones Company, 1917), 197.

12. Cram, Substance, 199.

13. William H. Jordy, American Buildings and their Architects: Progressive an Academic Ideals at the Turn of the Century (New York: Doubleday and Co., Inc., 1972), 79.

14. Lewis Mumford, Sticks and Stones: a study of American architecture and civilization (1924; 2nd revised ed. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1955), 147.

15. Turner, 129-131.

16. Charleston Weekly Plaindealer (Dedication Day edition, Sept. 1, 1899), np, [2].

17. Charleston Weekly Plaindealer (Normal Day edition, Sept. 1, 1899), np.

18. Charleston Weekly Plaindealer (Dedication Day edition, Sept. 1, 1899), np.

19. President Lord correspondence, October, 1901, folder 40, EIU archives.

20. “Dedication of Eastern Illinois State Normal School” (Charleston Daily Courier, August 29, 1899), 1.

21. Letter from Angus and Gindele to the Honorable Judge F.M. Youngblood, President of the Board of Trustees, Feb. 13, 1897, EIU archives. In that letter Angus and Gindele refer to a March 5, 1896, letter. That letter, which requested the changes, is undated and is also located in the EIU archives.

22. “Dedication” (Daily Courier, August 29, 1899).

23. Ibid.

24. Christopher Vernon, “Walter Burley Griffin, Landscape Architect,” in John S. Garner, ed., The Midwest in American Architecture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 217, 218.

25. Ernest L. Stover, Trees and Shrubs of the Campus, The Teachers College Bulletin, no. 89 (Charleston, July 1, 1925), 4.

26. A Catalogue of the Eastern Illinois State Normal School, Third Year, 1901-1902; Announcements for 1902, 1903 (Chicago: Rand McNally Press, 1901), 39.

27. ibid.

28. “Letter from Alumnus,” 5.

29. Letter from Walter B. Griffin to Livingston C. Lord, May 18, 1903, Lord correspondence, folder 2, EIU archives.

30. Griffin, who built up a successful Chicago practice, in 1906 designed the grounds for Northern Illinois State Normal School. In 1912 Griffin won an international competition to design the new capital of Australia at Canberra, and the midwest lost one of its most promising architects.

31. T.V. Smith and W.E.O. Clifford, Senate Committee Report on the Normal Colleges State of Illinois (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois State Teachers College, 1936), 7.

Old Main - Construction - Charleston - The Campus - A Future -

That Noble Project - A Building for the Ages - 1999-2000 Exhibit Gallery & Acknowledgments