|

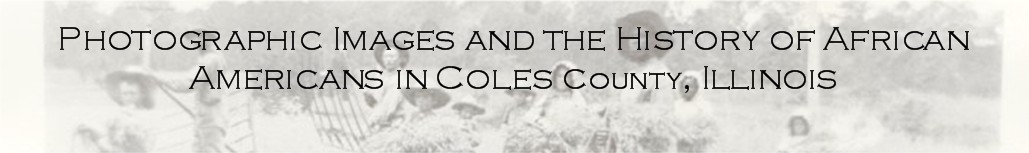

James D. Williams, DDC, Chiropractic Physician

and Certified Acupuncturist, Mattoon, Illinois.

|

|

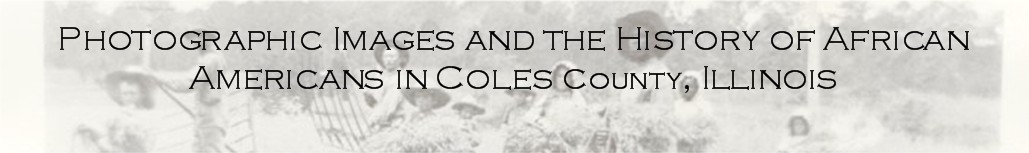

Mrs. Ona Norton was a Charleston, Illinois

community activist. She died in 1995 at age 101.

|

|

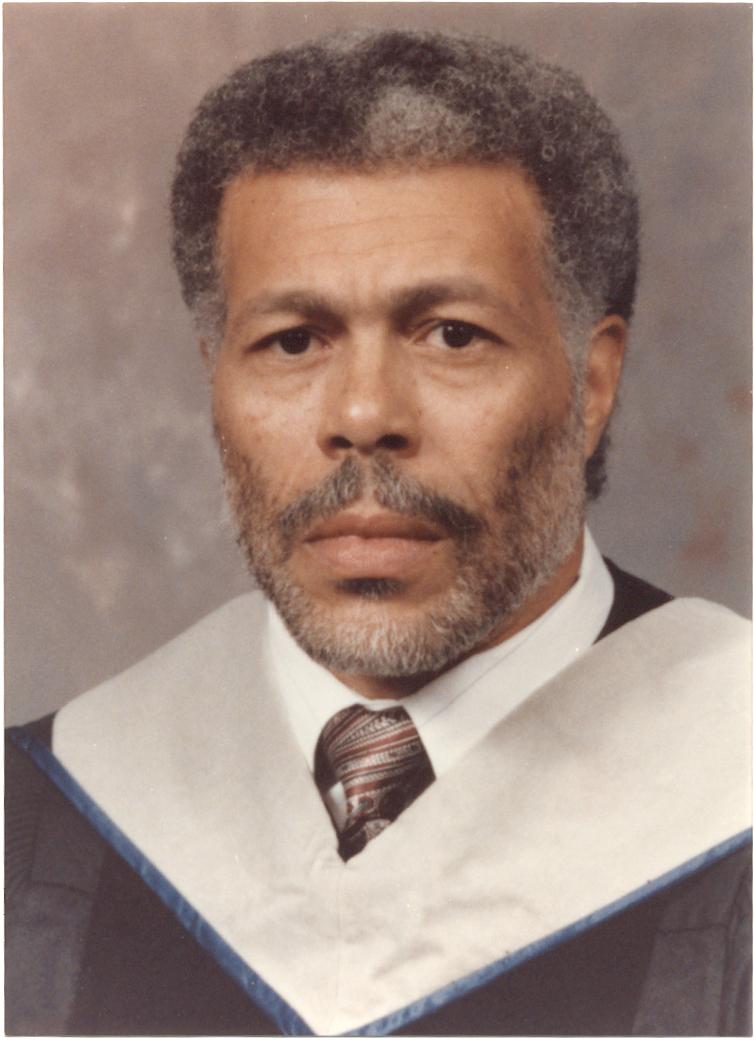

Kenneth H. Norton, Jr. and Annabel Norton's

Wedding Party, 1944.

|

|

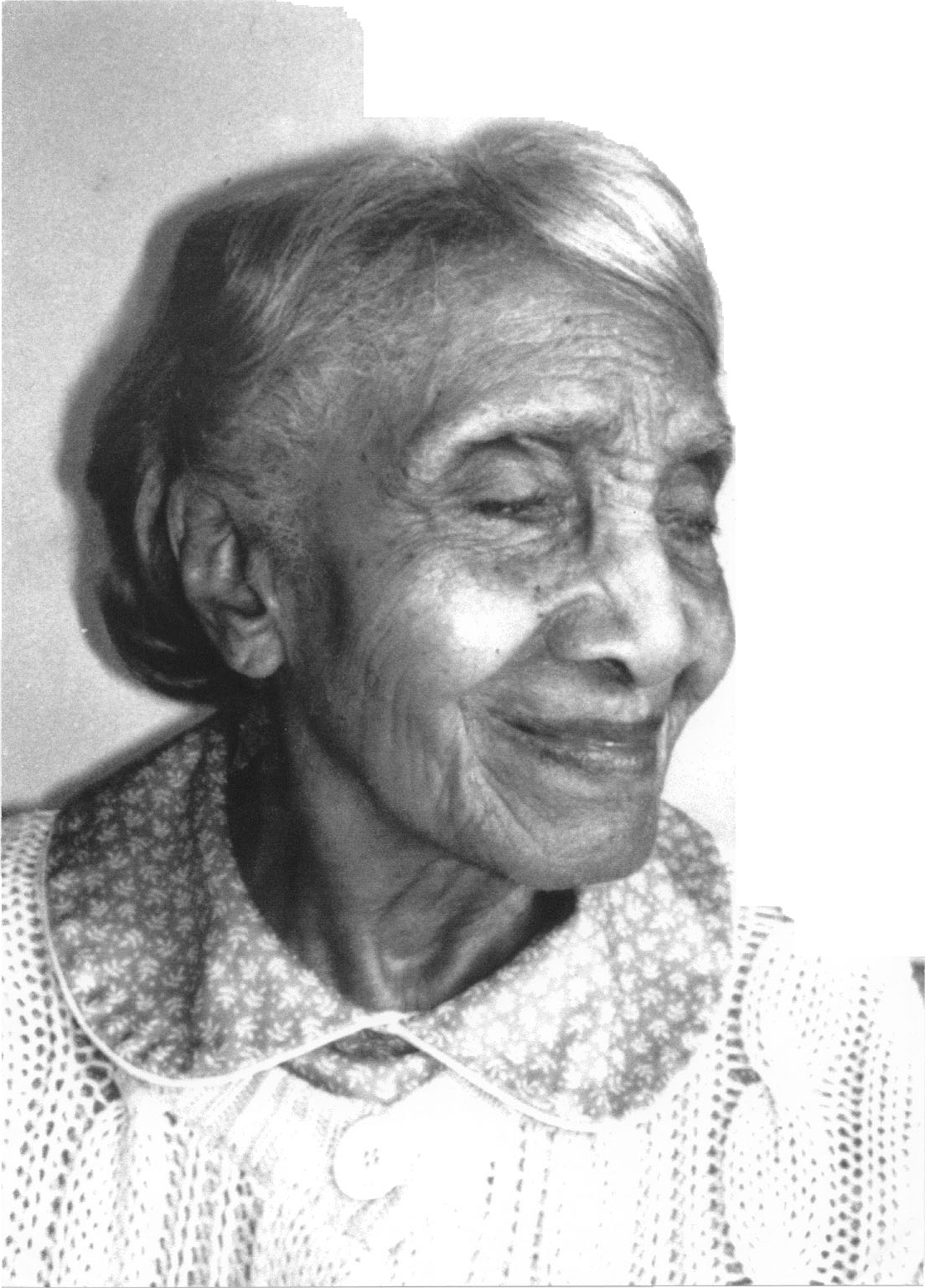

Mrs. Ona Norton with a group of EIU African

American students.

|

|

(left to right) Kenneth H. Norton, Sr., Ona

Norton, Kenneth H. Norton, Jr., and Minnie Portee, c. 1942.

|

|

Mrs. Ona Norton (left) and Mr. Kenneth H.

Norton, Sr.. For man years Mr. and Mrs. Norton helped black

EIU students find housing before housing was available to

them on campus.

|

|

The 1847 Matson Slave Trial in Charleston demonstrated

the tenacity of abolitionists in the county. The trial involved

Robert Matson, a Kentucky plantation and slave-owner and two Coles

County abolitionists, Dr. Hiram Rutherford and Gideon Ashmore. As

a practice, Matson brought slaves from his Kentucky plantation to

work in his Oakland farm which he called Black Grove. Matson appointed

a free black man Anthony Bryant the overseer of the farm. When it

came to Bryant's knowledge that Matson was planning to return Bryant's

wife, Jane Bryant, and four children back to Kentucky to sell them,

Anthony sought protection for his family from Gideon Ashmore and

Dr. Hiram Rutherford. Ashmore and Rutherford were two prominent

individuals among about thirty Coles County abolitionists of the

time. Following Matson's return to the county, he requested the

return of his slaves. But the slaves were later moved to the county

jail in Charleston on the orders of the Justice of the Peace, William

Gilman and in line with the laws of the state. The county billed

Matson the sum of $107.30 for the upkeep of the slaves. Based on

a writ of Babes Corpus, Ashmore applied to the Circuit Court for

the release of Jane Bryant and her four children. Matson filed a

counter suit against Ashmore and Rutherford claiming the sum of

$2,500 ($500 for each slave) as damages. Matson further claimed

that the slaves were not Illinois residents, and as a result were

not entitled to freedom. Ashmore and Rutherford on the other hand

responded by arguing that Jane and her children were not Matson's

property because the Illinois of 1818 declared slavery illegal in

the state. This set the stage for a trial in Charleston in October

1847.

While Robert Matson engaged Usher F. Binder and

Abraham Lincoln to defend him, the slave owner. As Easter-Shick

and Clark noted, "[i]t is a curious thing that Lincoln, who

disliked slavery and would one day be known as the "Great Emancipator,"

would appear as an attorney for a slave owner. Whatever his reason,

it was a subject that would continue to puzzle historians."

(21) Whereas it may be puzzling to some, it is possible to offer

some explanations for Lincoln's action. Local legend has it that

Lincoln accepted to defend Matson because he (Lincoln) was determined

to lose the case in order to spite the slave owner. But there is

no evidence to back up this legend. In addition to the fact that

Lincoln had already accepted Matson's briefs before Rutherford consulted

him, a more plausible explanation is that Lincoln's views on slavery

might have changed over time. While he might have been ambivalent

about slavery and the status of slaves in 1847, his views on the

issue had clearly changed when he became the president of the country.

Despite the fact that Lincoln did not categorically make statements

favoring slavery in America, he did not recognize the equality of

blacks and whites. At the Fourth Lincoln-Douglas Debate, September

18, 1858, in Charleston, Illinois, Lincoln made the following pronouncement:

While I was at the hotel to-day an elderly gentleman

called upon me to know whether I was really in favor of producing

a perfect equality between the negroes and white people. [Great

laughter]...I will say then that I am not, nor ever been in favor

of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of

the white and black races, [applause]— that I am not nor ever

have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of

qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people;

and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference

between white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid

the two races living together on terms of social and political equality...

Judge Douglas has said to you that he has not been able to get from

me an answer to the question whether I am in favor of negro citizenship.

So far as I know, the Judge never asked me the question before.

[Applause.] He shall have no occasion to ever ask it again, for

I tell him very frankly that I am not in favor of negro citizenship.

[Renewed applause.] ...Now my opinion is that the different States

have power to make a negro a citizen under the Constitution of the

United States if they choose. The Dred Scott decision decides that

they have not that power. If the State of Illinois had that power

I should be opposed to the exercise of it. [Cries of "good,"

"good," and applause.] That is all I have to say about

it. (22)

|